When does political theatre cross into a national security concern?

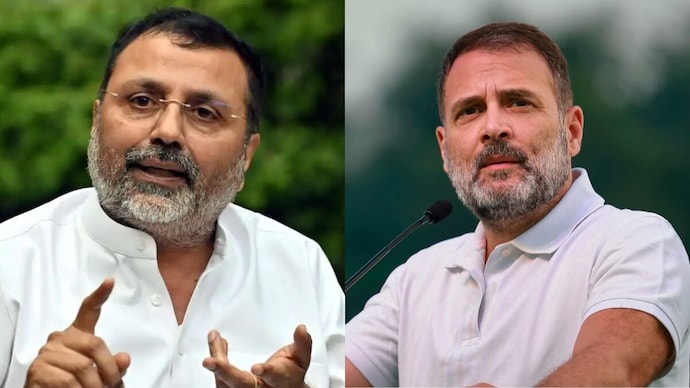

That is the uncomfortable question now confronting the nation after excerpts from an unpublished memoir of former Chief of Army Staff Manoj Mukund Naravane surfaced in public discourse — and were cited on the floor of the Lok Sabha by Leader of the Opposition Rahul Gandhi.

The controversy is no longer about political point-scoring. It is about process, propriety, and the sanctity of institutions.

Every government servant in India, under established conduct rules, is required to obtain prior clearance before publishing material relating to official duties — particularly when such material may involve national security, defence preparedness, or classified operations.

The armed forces are not exempt from this discipline. If anything, the standards are higher.

The key question is straightforward:

Was due clearance obtained before the manuscript was shared externally?

Even if the book is unpublished, how did portions enter public circulation? Who had access? Was the manuscript vetted by the competent authority?

These are not political questions. They are administrative and legal ones.

If permission was sought and granted, the government must clarify.

If not, then the matter demands scrutiny.

The publisher associated with the manuscript, Penguin Random House India, issued a statement distancing itself from political interpretations of the text.

But can a publisher merely issue a disclaimer and move on?

Publishing defence-related memoirs is not the same as publishing fiction. Publishing houses are expected to ensure that:

- Legal vetting has been completed

- Author permissions comply with service rules

- No classified information is inadvertently revealed

If unpublished content is already circulating in the public domain, one must ask:

- Who printed it?

- Was it an advance review copy?

- Was it leaked?

- Was it shared informally?

- Was the government informed?

A disclaimer may address reputational concerns. It does not automatically settle questions of compliance.

More troubling is the fact that excerpts from an unpublished manuscript were waved in the Lok Sabha.

Parliament is not a press conference. It is the highest deliberative body of the Republic.

When a Member of Parliament — particularly the Leader of the Opposition — cites unpublished material, certain standards apply:

- Has the document been authenticated?

- Is it in the public domain officially?

- Has the author confirmed its accuracy?

- Has it been vetted by relevant authorities?

As an aspirant to the highest executive office in the country, Rahul Gandhi cannot afford procedural casualness. Parliamentary privilege is not a shield for bypassing due diligence.

The issue is not ideological. It is institutional.

India’s armed forces operate in one of the most volatile security environments in the world. Strategic decisions, operational assessments, and internal deliberations are rarely meant for premature public debate — especially if not officially cleared.

Former chiefs retain influence. Their words carry weight internationally.

Unverified or prematurely circulated accounts can:

- Impact troop morale

- Affect diplomatic engagements

- Be exploited by hostile narratives

- Undermine strategic credibility

Even the perception of internal discord can be weaponised by adversaries.

This is why service conduct rules exist.

The controversy did not emerge organically. It was amplified in Parliament. Proceedings were disrupted. Accusations flew. Television studios erupted. Parliament time — funded by taxpayers — was lost.

The cost of a stalled Parliament is not metaphorical. It is measurable in crores.

If the controversy arose from:

- Premature sharing of a manuscript,

- Irresponsible citation of unpublished material,

- Or failure of procedural compliance,

Then accountability must follow — regardless of rank, office, or political affiliation.

To be clear: any action must follow due process. A preliminary inquiry, if warranted, should establish:

- Whether mandatory clearance was obtained.

- Whether classified or sensitive material was involved.

- How the manuscript entered circulation.

- Whether parliamentary norms were violated.

If no rules were broken, transparency will settle the matter.

But if rules were breached, then precedent demands action.

No democracy can selectively enforce discipline.

The Modi government now faces a choice.

It can allow the controversy to fade into partisan shouting.

Or it can demonstrate institutional seriousness by ordering a fact-based inquiry.

This is not about targeting individuals. It is about reinforcing norms.

If a former Army Chief bypassed procedure, it sets a precedent.

If a publisher neglected compliance, it sets a precedent.

If a senior parliamentarian relied on unverified documents to stall proceedings, it sets a precedent.

And precedents shape democracies.

India’s armed forces are among the most trusted institutions in the country. Parliament is the embodiment of the people’s sovereignty. Publishing houses play a vital role in shaping public discourse.

None of them should become arenas of procedural ambiguity.

The Modi government must not shy away from establishing the facts and acting — firmly, legally and transparently — if any breach is proven.

Taxpayers fund Parliament. Citizens trust the armed forces. National security is not a debating prop.

Storms may be political.

Institutions must remain constitutional.