The sudden and dramatic return of Tarique Rahman, acting chairman of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and scion of one of Bangladesh’s two dominant political dynasties, marks a pivotal moment in the nation’s political evolution. After nearly 17 years in exile, Rahman arrived in Dhaka to a massive, emotional welcome — an event that could reshape Bangladesh’s political landscape as fiercely contested elections approach in February 2026.

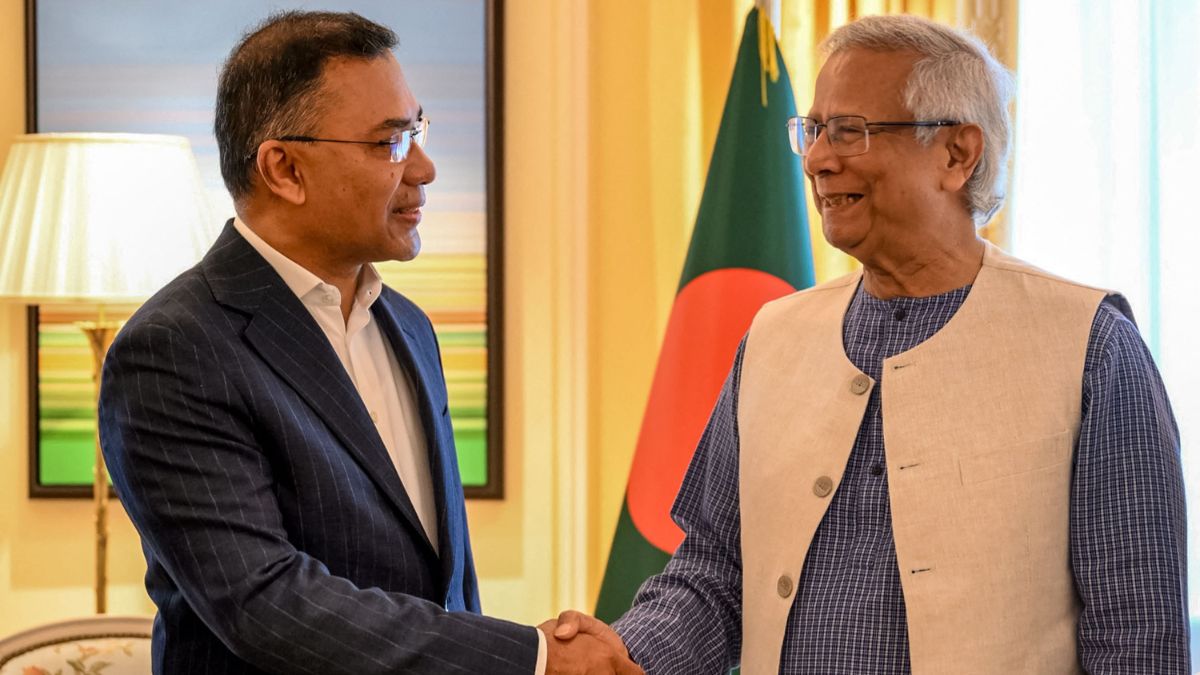

Bangladesh today is a country experiencing rare instability. The long-dominant Awami League — led for decades by Sheikh Hasina — was ousted in 2024 after mass unrest, leading to an interim government under Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus. The political space, once tightly controlled by Hasina’s party, is now in flux. The Awami League has been banned from contesting the upcoming elections, fueling controversy and fears that the polls may lack true inclusiveness.

Amid this upheaval, attacks on press freedom and recurring violence — including mob attacks on newspaper offices — have raised deep concerns about stability and democratic norms.

Tarique Rahman is not a newcomer to Bangladesh’s political firmament. The son of former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia and grandson of President Ziaur Rahman, his family has alternated power with the Awami League for decades. His own political career has been controversial: for years, he lived in London, avoiding more than 80 criminal cases in Bangladesh, including a 2004 grenade attack case and corruption charges that his party consistently described as politically motivated. Recent legal changes — following Hasina’s removal — saw all those convictions overturned, legally clearing the path for his return.

Rahman’s return is clearly timed for political impact, with the elections just weeks away and the BNP positioning itself as the principal challenger to the status quo. BNP leaders openly view his presence as critical to unifying their fractured ranks, consolidating support, and reclaiming political relevance.

One of the most pressing questions is whether his ascent will revive Bangladesh’s democratic ethos — or entrench another form of factional rule.

Supporters argue that Rahman’s return fills a leadership vacuum at a time when governance has been in disarray, boosting the prospects of a relatively competitive multi-party system after years of polarized one-party dominance. Newer parties such as the National Citizen Party (NCP), which emerged from the 2024 citizen uprising, have welcomed Rahman’s homecoming and view it as reenergizing parliamentary democracy.

Yet sceptics — including remnants of the Awami League and student wings — dismiss this optimism. They warn that Rahman’s re-entry may be part of a strategic back-door compromise with the interim government aimed more at staging a one-sided election than restoring vibrant democracy. They point to the exclusion of major competitors like the Awami League as evidence that the political playing field remains fundamentally uneven.

In practical terms, Bangladesh’s democratic revival now hinges on whether the elections can be free, fair, and genuinely competitive, and whether Rahman commits to institutional governance rather than factional dominance. The absence of a full spectrum of political voices — especially the barred Awami League — remains a structural concern.

Pre-election surveys suggest the BNP, under Rahman’s stewardship, is positioned to secure a significant number of seats, possibly emerging as the leading party in the national parliament.

However, several challenges remain:

- Fierce competition from the Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami and allied groups, which historically have been ideological partners or rivals at different times.

- The absence of the Awami League — long a crucial stabilizing and mass political force — threatens to skew the electoral landscape.

- Youth sentiment, embodied in the NCP and street movements, may not align neatly with traditional BNP constituencies, leaving the BNP dependent on more established — and sometimes conservative — vote banks.

These dynamics make a BNP victory likely but not assured, and the shape of government could hinge on post-election coalitions and the extent of voter engagement.

Perhaps the most geopolitically consequential aspect of Rahman’s return is its impact on Bangladesh’s relationship with India.

Under Hasina, Dhaka maintained historically close ties with New Delhi — cooperation that touched trade, security, and connectivity. But recent years, especially under the interim government, saw a tilt that included warmer gestures toward Pakistan and rhetoric critical of India’s influence.

Rahman’s own public stance has been nuanced. He has articulated a “Bangladesh First” foreign policy — signalling that Dhaka’s decisions will prioritize sovereign interests and avoid undue alignment with any external power, whether India or Pakistan.

For India, this is a double-edged sword. On one hand, a more predictable and democratic partner in Dhaka — led by the BNP rather than an unstable interim regime — could stabilise bilateral ties. On the other hand, the rhetoric of equidistance implies Dhaka will resist being drawn too closely into the Indian strategic orbit.

Delhi’s engagement so far has been cautious but positive: Indian leaders have publicly expressed support for political stability in Bangladesh, including concern for Khaleda Zia’s health — gestures warmly received by the BNP.

Tarique Rahman’s return is more than a political comeback — it is a defining inflection point for Bangladesh’s governance, democratic aspirations, and regional posture.

If he can harness his personal legitimacy and the BNP’s organisational strength to facilitate inclusive elections, strengthen parliamentary norms, and broaden political space beyond entrenched factionalism, Bangladesh may be on the cusp of a genuine political reset. But if the upcoming polls unfold without key voices and under suppressed competition, this moment risks becoming merely another chapter in the country’s long saga of power struggles rather than a renewal of democratic promise.

In the tumultuous theatre of South Asian politics, the stakes are high — not just for Bangladesh, but for India and the region’s future stability. The coming months will reveal whether Rahman’s return is a beacon for democratic resurgence or simply another turn in a familiar cycle of political drama.