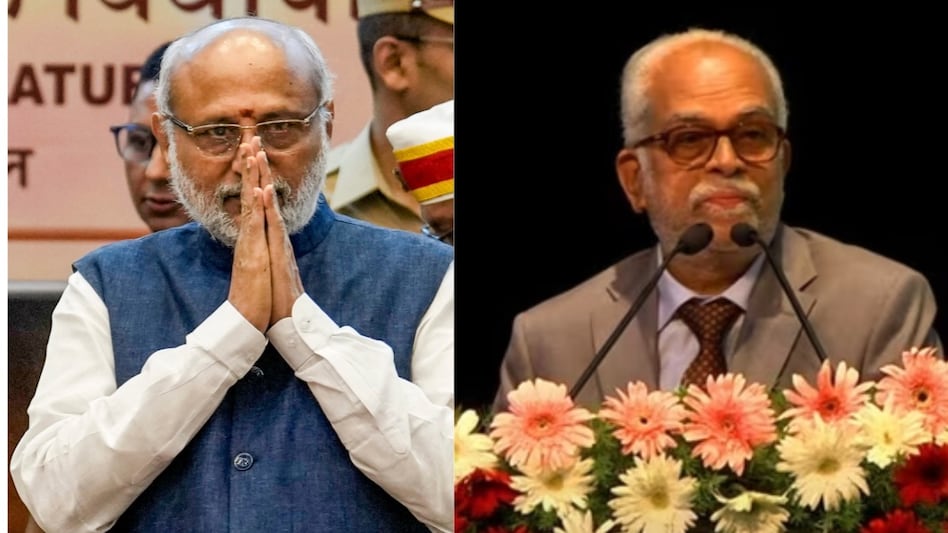

India’s political arena is gearing up for a high-stakes vice-presidential election tomorrow. On one side stands the NDA’s candidate, C. P. Radhakrishnan—a seasoned BJP veteran from Tamil Nadu. On the other is Justice B. Sudershan Reddy, a Telangana-born former Supreme Court judge, fielded by the INDIA bloc.

According to the Election Commission, the 2025 vice-presidential electoral college comprises 782 current voters: 543 elected Lok Sabha members (with one vacancy) and 233 elected plus 12 nominated Rajya Sabha members (with five vacancies).

On the numbers, the NDA enjoys a commanding edge. Reports suggest the ruling alliance has the backing of 439 MPs, against roughly 324 for the INDIA bloc—even before factoring in expected abstentions from the BJD and BRS, both likely to sit out. In other words, Radhakrishnan’s victory looks all but assured.

This contest, however, is not without its novelty. For the first time since Independence, both candidates hail from South India—Tamil Nadu and Telangana—marking a rare “southern showdown” and underscoring the growing imprint of the region on national leadership.

Justice Reddy has framed his candidature around ideals rather than numbers. Calling for dignity and restraint, he urged against personal attacks, casting this contest as a “clash of ideas” instead of a mere power struggle. He has warned of democratic erosion under unchecked majoritarianism, though his own record is not free of controversy—notably his judgment in the Salwa Judum case, which endorsed a state-backed militia against left-wing extremists.

By contrast, Prime Minister Modi personally introduced Radhakrishnan to NDA MPs, praising his integrity, simplicity, and sporting spirit—qualities intended to lend weight and credibility to his candidacy.

Given the arithmetic, many observers question whether the INDIA bloc should have contested at all. Would it have been wiser, some ask, to concede gracefully in the name of institutional decorum, rather than fight a losing battle? By challenging the inevitable, the Opposition risks reinforcing perceptions of irrelevance.

Yet, the INDIA bloc’s decision was not without intent. By nominating a jurist of perceived neutrality, it sought to project a principled stand—offering a symbolic defence of constitutional values even in the face of certain defeat.

Still, with tomorrow’s vote looming, only two variables could shift margins:

-

Cross-voting: The secret ballot system allows MPs to stray from party lines.

-

Abstentions: With the BJD and BRS expected to remain neutral, some fluctuation is possible. But the NDA’s 115-vote cushion makes minor surprises inconsequential.

The truth is this election is less a battle of ballots and more a mirror of India’s evolving political landscape. Justice Reddy’s bid, while noble in rhetoric, never had the numbers. The INDIA bloc’s idealism was unable to translate into electoral viability.

The symbolism of two southern candidates cannot mask the deeper reality: the Opposition continues to struggle in converting lofty talk of dissent, debate, and constitutional duty into meaningful political strength. In the end, tomorrow’s contest may well reinforce what many already suspect—that India’s Opposition is still fighting more for relevance than for results.