In the shadowy world of defence technology, the most potent weapons are often the ones you never see — or hear. One such system, cloaked in secrecy and whispered about in defence circles, is India’s KALI, short for Kilo Ampere Linear Injector. Developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) in collaboration with the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), this isn’t your typical missile or laser. Instead, KALI is a directed-energy behemoth capable of crippling enemy electronics in the blink of an eye, without a single explosion.

KALI’s story began in 1989, not as a weapon, but as a project for industrial applications such as X-ray imaging and materials research. But as the Cold War gave way to a new era of high-tech warfare, its potential for military use became too significant to ignore. Scientists realised that KALI’s Relativistic Electron Beams (REBs) — when converted into intense pulses of X-rays or microwaves — could be weaponised to devastating effect.

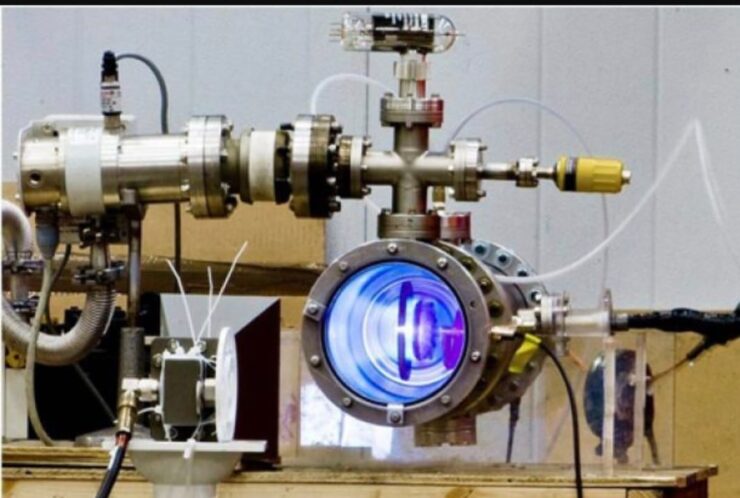

Traditional weapons rely on kinetic destruction — explosives, shrapnel, impact. KALI takes a different route. It generates bursts of high-energy electron beams, which are converted into electromagnetic radiation in the microwave or X-ray spectrum. These pulses fry the delicate electronics inside missiles, aircraft, drones, or satellites, rendering them useless without blowing them to pieces.

This makes KALI the perfect “soft-kill” weapon. Instead of physically destroying a target, it kills the brain — the guidance computers, sensors, and communications systems, leaving a dead hulk in the sky. Against the backdrop of modern, electronics-heavy warfare, that is an extraordinarily powerful advantage.

Over the decades, KALI has evolved through several versions: KALI-80, KALI-200, KALI-5000, and the fearsome KALI-10000. These “Single Shot Pulsed Gigawatt Electron Accelerators” have steadily increased in power and range.

The KALI-5000, for instance, can produce electron pulses with a staggering 40 gigawatts of peak power — enough to disable advanced electronics from a significant distance. In combat terms, that means an incoming missile or an enemy AWACS aircraft could be blinded and crippled before it even knows it’s under attack.

There’s a reason Indian scientists consider KALI more lethal than many laser-based systems. Lasers physically burn or drill through a target, which takes precious seconds and risks incomplete destruction. KALI’s microwave bursts don’t need to burn anything — they instantly short-circuit and overload electronics, making them faster and, in many cases, more reliable.

Think of it as the difference between cutting the strings of a puppet and simply switching off the puppet master’s brain.

The potential uses for KALI are vast:

- Anti-Missile Defence: By frying guidance systems mid-flight, KALI could neutralise ballistic or cruise missiles long before impact.

- Electronic Warfare: Enemy communication lines and radar installations could be rendered useless, creating battlefield chaos.

- Anti-Satellite Operations: As warfare increasingly moves into space, KALI could blind or disable adversary satellites, crippling their reconnaissance and navigation capabilities.

- EMP Protection: KALI’s technology could also help safeguard Indian assets from electromagnetic pulses generated by nuclear detonations or hostile EMP weapons.

Some analysts speculate that KALI could be mounted on airborne platforms like the IL-76 or C-17 Globemaster, giving it a mobile reach across theatres of operation.

Given the classified nature of the project, official confirmation of operational tests is scarce. Yet rumours abound. One persistent claim is that a 2012 avalanche in Siachen, which buried Pakistani positions, may have been triggered by a KALI test. Others whisper that KALI has already been integrated into India’s defensive grid in ways the public cannot yet imagine.

Whether these stories are fact or folklore, they add to the weapon’s aura — and perhaps serve as a subtle warning to adversaries.

Directed-energy weapons are not India’s exclusive domain. The United States has tested the CHAMP (Counter-electronics High-powered Microwave Advanced Missile Project), capable of taking out enemy electronics without collateral damage. China is rumoured to be pursuing similar systems. However, what makes KALI notable is that it’s homegrown, scalable, and — crucially — built for India’s specific defence challenges against Pakistan and China.

In the chessboard of geopolitics, deterrence is often about perception as much as reality. KALI’s mere existence, confirmed or not, changes the risk calculus for any hostile actor considering electronic or missile warfare against India.

It’s silent, invisible, and doesn’t rely on expensive, non-renewable ammunition. In a future conflict, KALI could be the ace up India’s sleeve — taking out threats without leaving a trace of smoke or flame, but with devastating effect.

As technology evolves and warfare moves deeper into the electromagnetic domain, KALI stands as a symbol of India’s leap into the front ranks of modern military capability. The enemy may never see it coming — and that’s exactly the point.