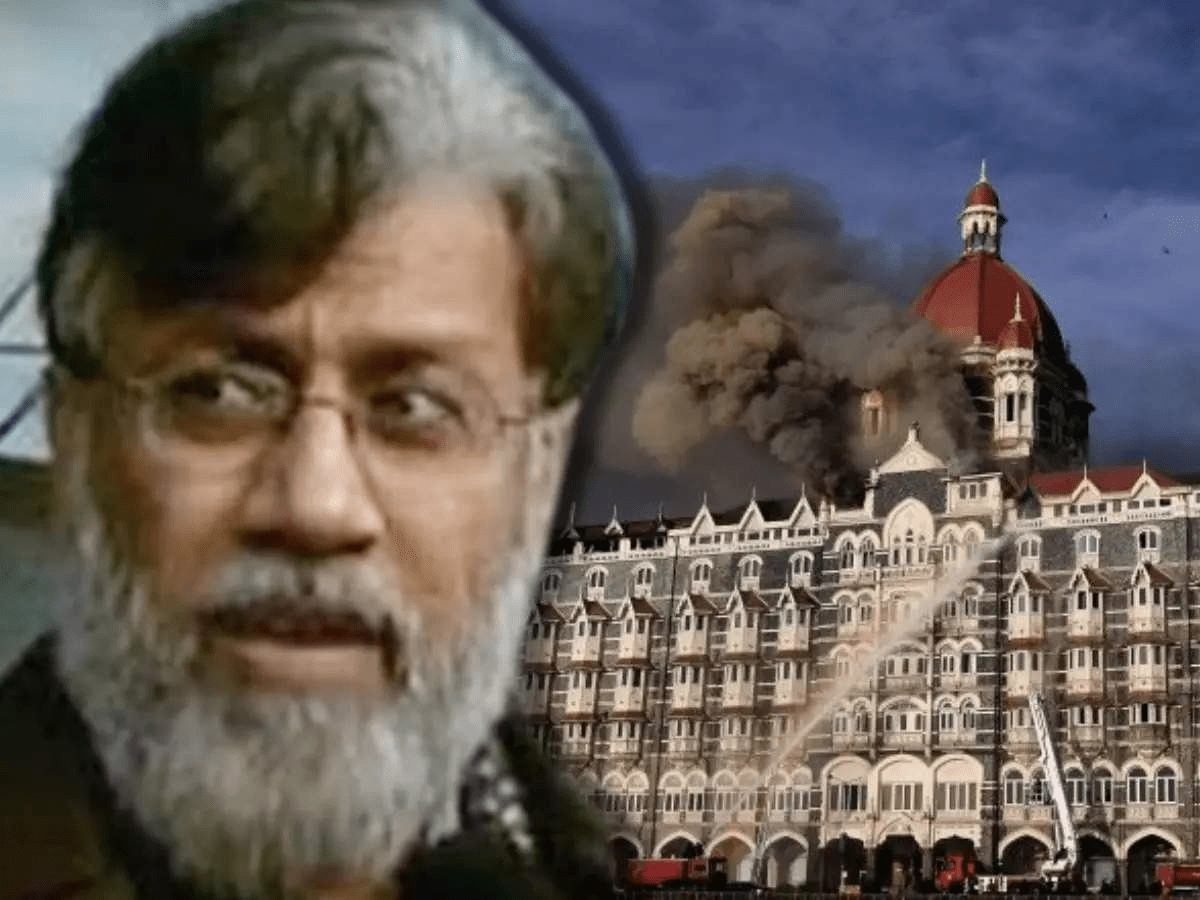

In a landmark development that marks a major diplomatic and legal victory for India, Tahawwur Rana—the man accused of playing a key role in the deadly 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks—will finally face Indian justice. After years of legal wrangling and international coordination, the U.S. Supreme Court has refused to entertain Rana’s plea against extradition, clearing the final hurdle for his transfer to India.

A six-member team from the National Investigation Agency (NIA) is flying him back on a special aircraft tomorrow, and high-security facilities in Delhi and Mumbai are already being prepared to house the high-value detainee.

A Pakistani-Canadian national, Rana was not just another cog in the terror machinery—he was a key enabler. A close associate of David Coleman Headley (aka Dawood Gilani), Rana is accused of helping facilitate reconnaissance missions in Mumbai under the guise of legitimate business activity. The plot was orchestrated by Pakistan-based terror outfit Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), with alleged backing from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

Rana, who once served as a military doctor in Pakistan, helped Headley open a fake immigration office in Mumbai, which served as the cover for collecting intelligence on possible targets. Between 2007 and 2008, Headley made five trips to India with logistical and financial support from Rana. According to U.S. court documents, Rana not only enabled these missions but also expressed chilling satisfaction at the carnage that unfolded on November 26, 2008, where over 160 people were killed.

The road to Rana’s extradition has been long and fraught with legal obstacles. India officially requested his extradition in December 2019. By June 2020, a complaint was filed seeking his provisional arrest. It was in February 2020 that then-President Donald Trump confirmed Rana would be extradited, but Rana’s legal team kept filing appeals to delay the process. The U.S. Supreme Court’s final dismissal of his plea this week ended the last avenue of resistance.

This extradition is more than symbolic. It’s a diplomatic coup for India, which has often struggled to bring foreign-based terror operatives to justice. It also reinforces the growing trust and legal cooperation between India and the United States on counterterrorism. Rana’s return shows that while it may take time, justice for global terror crimes is not out of reach.

As expected, Pakistan has denied any association with Rana, continuing its standard playbook of disavowing nationals involved in international terrorism. The Sharif government has issued no formal statement, a silence that speaks volumes. Despite overwhelming evidence—including testimonies from Headley himself and documents submitted in both Indian and U.S. courts—Pakistan remains in denial about its institutional complicity in cross-border terrorism.

While India is witnessing a moment of long overdue justice, political bickering back home continues. The Congress party, which was in power during the 26/11 attacks, appears more preoccupied with internal dissent and electoral anxieties—ironically, while camped in Ahmedabad, the home turf of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Rather than acknowledging a diplomatic win for India, Congress leaders seem busy sulking over their uncertain future.

The extradition should serve as a moment of national unity. Yet, predictably, political narratives are diverging. What ought to be framed as a collective triumph in India’s global fight against terror is being diluted by partisan distractions.

The Rana extradition sends a powerful message: the long arm of justice, when guided by international cooperation, can reach across borders. It is also a signal to global terror networks that time, distance, and nationality won’t shield them from accountability.

For India, this moment is not just about the past—it is a reaffirmation that its commitment to justice for 26/11 will not fade with time. It’s a stern warning to those who believe terror plots can be buried in diplomatic inertia.

Tahawwur Rana’s arrival in India isn’t just the extradition of a man—it’s the return of unfinished justice. While India has succeeded in bringing him back, the onus is now on the Narendra Modi government to fast-track the trial and ensure justice is delivered. That means pushing for the harshest penalty—sending him to the gallows. But ultimately, it all hinges on the Supreme Court and how swiftly it acts without getting bogged down by endless review petitions. Justice delayed is justice denied—and this time, it must be time-bound.