The recent controversy surrounding former Delhi High Court Judge Yashwant Verma and the staggering amounts of cash discovered at his residence has reignited the debate over the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). The Supreme Court scrapped the NJAC, asserting that the collegium system represents the ‘will of the people.’ But does it? Or is this simply an unchecked power grab by the judiciary?

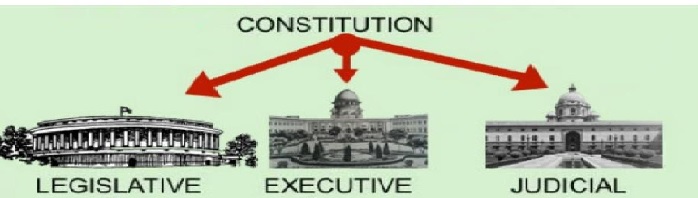

Let’s be clear: In a democracy, the ‘will of the people’ is represented by elected representatives in Parliament, not by unelected judges who self-appoint successors through an opaque and unaccountable collegium system. The framers of the Constitution, led by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, envisioned a system where judicial appointments were made through a transparent process, balancing independence with accountability. That was the NJAC—a body consisting of elected representatives with a constitutional obligation to consult the Chief Justice of India, not to seek his concurrence.

Yet, the Supreme Court unilaterally dismantled NJAC, clinging to its self-appointed supremacy over judicial appointments. The excuse? That judicial independence would be compromised if politicians had any say. But let’s not mince words—what we have now is not independence but an incestuous, unaccountable oligarchy where judges handpick their successors without public scrutiny.

This hijacking of constitutional intent was not without opposition. The late legal stalwart Soli Sorabjee strongly advocated the NJAC’s restoration, recognizing that the collegium system was fundamentally flawed. Former Solicitor-General Mukul Rohatgi echoed this view, exposing the judiciary’s deliberate misinterpretation of ‘consultation’ as ‘concurrence,’ twisting the Constitution to fit its narrative.

The timing of this controversy is telling. More than 25 bar associations have demanded Verma’s impeachment, and the Bar Council of Allahabad has gone on indefinite strike, rejecting his transfer to the Allahabad High Court. They want an independent investigation, not an internal whitewashing by the collegium. Even Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar, in his capacity as Rajya Sabha Chairman, has initiated discussions with opposition and ruling party leaders on potential impeachment proceedings. The push for accountability is gaining momentum, but will it be enough to dismantle the entrenched judicial cartel?

The collegium’s real fear is not about protecting judicial independence—it’s about self-preservation. With Chief Justice Rajiv Khanna set to retire, his likely successors—Justices B.R. Gavai, Surya Kant, A.S. Oka, and Vikram Nath—may see NJAC as a direct threat to their ascension. If NJAC returns, their carefully curated career trajectories could be disrupted. This is not about the Constitution or democracy; it’s about power.

The judiciary cannot continue to operate in a vacuum, immune from scrutiny. The cash scandal involving Justice Verma is just a symptom of a deeper disease—an unaccountable system that shields judges from the consequences of their actions. If India is serious about judicial reform, the first step is to restore NJAC and end the collegium’s unchecked dominance. Parliament must assert its rightful authority and remind the judiciary that the real ‘will of the people’ is not a judicial echo chamber but the elected representatives of the people.

The choice is clear: continue with a closed-door judicial monopoly or embrace democratic accountability. The time for Parliament to act is now.