Banakacherla dispute demands dialogue, not drama

In a mature democracy, especially in a federal setup like India’s, disputes—no matter how contentious—are meant to be resolved through negotiation, transparency, and consensus-building. When issues as vital as inter-state river water sharing become hostages to political grandstanding, the real losers are not politicians but the people. The fresh row over the Banakacherla project is a textbook example of how political expediency trumps public welfare.

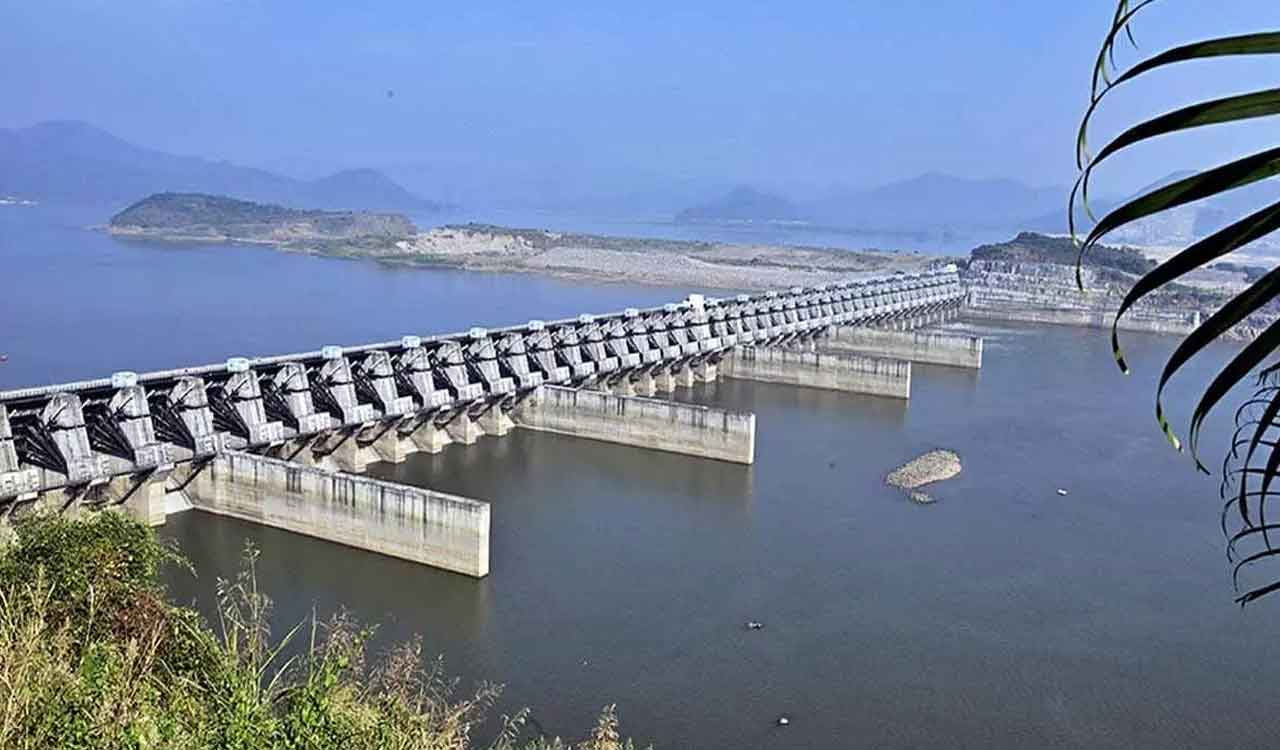

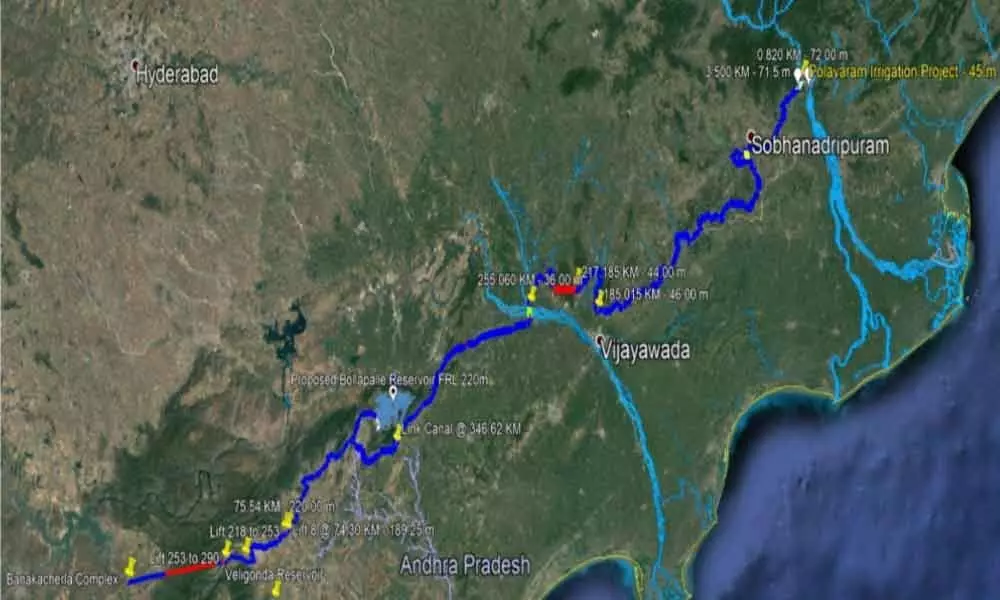

At its core, the Banakacherla project is an ambitious interlinking proposal to divert surplus floodwaters from the Godavari basin to the drought-prone regions of Rayalaseema, particularly Kadapa and Kurnool. The plan involves diverting water from Polavaram to the Krishna basin, and via tunnels and canals through ecologically sensitive areas, into Banakacherla. Andhra Pradesh argues that the project will utilize water otherwise flowing wastefully into the sea, in line with the Andhra Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2014.

Telangana, however, sees red. It has strongly opposed the project, asserting it violates both the Reorganisation Act and several inter-state agreements. Telangana contends that there is no such thing as “surplus” water in the Godavari, and that Andhra Pradesh has proceeded without proper environmental clearances, impact assessments, or necessary consultations with the Central Water Commission and river tribunal authorities.

These concerns are not baseless. Environmentalists have flagged serious ecological risks: the possible salinity intrusion in delta regions, harm to agriculture and fisheries, and destruction of wildlife habitats in the Nallamala forests. The Union government’s own Environmental Expert Committee recently denied clearance to the project, citing both procedural and environmental violations.

Given the complex legal, environmental, and human dimensions involved, any unilateral attempt to rush or stall the project must be viewed with caution. Yet, even more dangerous is politicising it for regional one-upmanship. The Telangana Chief Minister A. Revanth Reddy’s decision to boycott a crucial Jal Shakti Ministry meeting on the issue is nothing short of irresponsible.

Boycotting dialogue achieves nothing. If anything, it weakens Telangana’s legitimate case. A chief minister walking away from the table on an issue as critical as water security is not a sign of strength—it is a dereliction of duty. By absenting himself from the meeting, Revanth Reddy squandered an opportunity to put forth Telangana’s case forcefully, demand scientific clarity, and seek assurances for his state’s rightful water share.

This also reveals a worrying political pattern. Revanth, once a product of the Telugu Desam Party and groomed by none other than Andhra CM N. Chandrababu Naidu himself, has, after joining Congress, adopted the party’s combative style of politics. His rise to the CM’s chair—reportedly handpicked by the Congress high command despite internal dissent—has perhaps emboldened him to play the regional victim card to cement his image at home.

But whipping up regional passions on an emotive issue like river water won’t win long-term political dividends. What it risks is damaging an already fragile inter-state relationship. Naidu, for his part, must also ensure that AP’s moves are grounded in legal clarity and ecological prudence, not majoritarian political muscle. The ₹80,000-crore project cannot move forward without addressing the ecological costs and without building consensus—especially when over 40,000 acres, including forest land, are involved.

Water disputes are among the most volatile issues in Indian federalism. They are deeply linked to agriculture, livelihoods, and basic survival. This makes it all the more imperative for leaders on both sides to rise above party lines, personal egos, and political score-settling.

India has seen this movie before—with the Cauvery dispute between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, the Mullaperiyar dam between Tamil Nadu and Kerala, and others. Each of those dragged on for decades, not because technical solutions didn’t exist, but because political will did not.

The Banakacherla issue cannot be allowed to travel that same dead-end road. Both Telangana and Andhra Pradesh must sit across the table, backed by expert panels, environmental scientists, and legal experts. The Centre must play its role not as a mute observer but as an active mediator, ensuring the spirit of the Reorganisation Act is honoured in letter and intent.

In the end, water doesn’t vote—but people do. And when those people start losing crops, livelihoods, and security due to elite political battles, they remember. It’s time for both Revanth Reddy and Chandrababu Naidu to stop playing to their galleries and start doing what chief ministers are elected to do—govern, not grandstand.